The Value of The Death of An Original

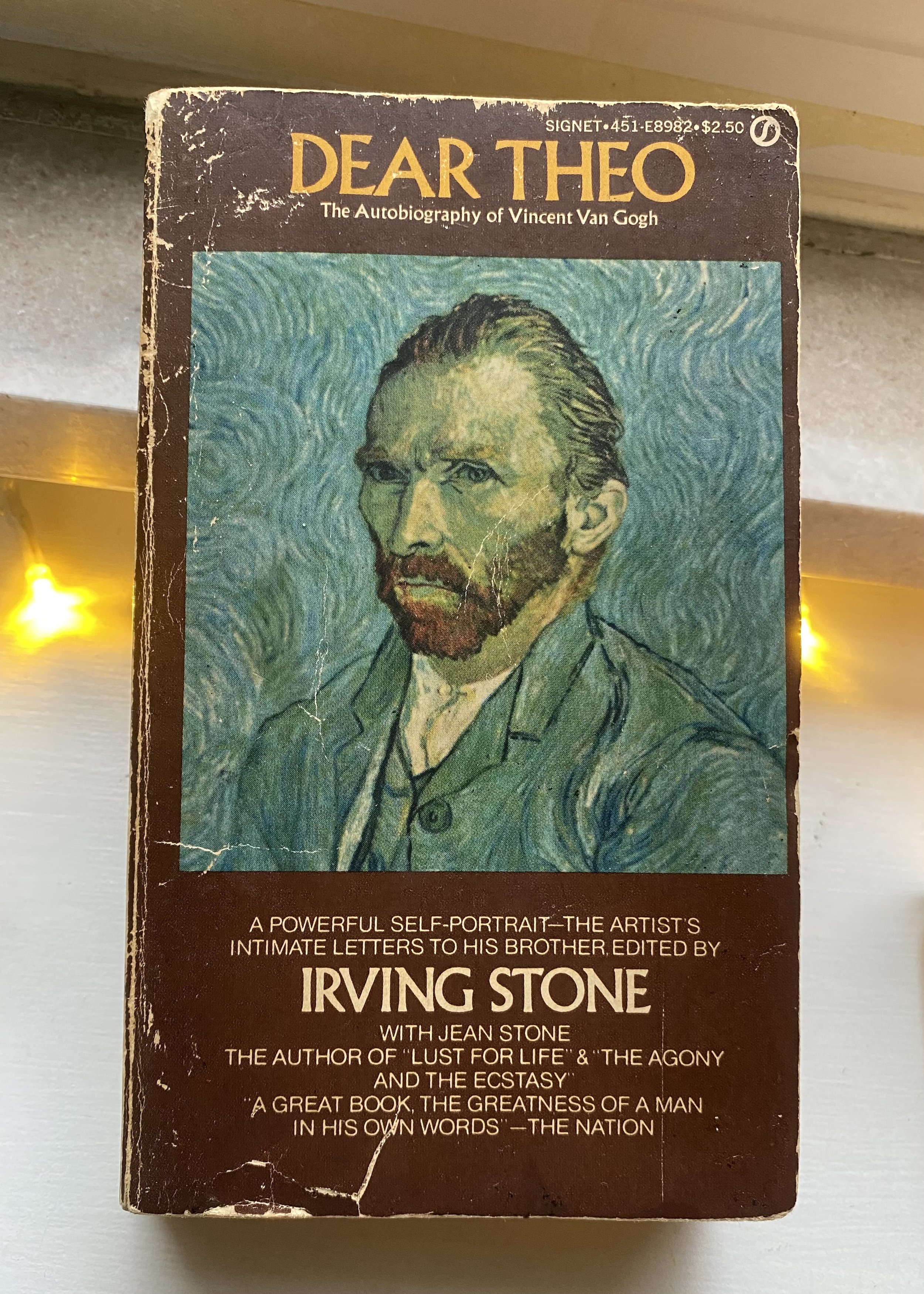

Dear Theo, The Autobiography of Vincent Van Gogh, edited by Irving Stone

In his autobiography, Dear Theo, Vincent Van Gogh intimately pens the artist’s struggle to his brother. “Painters … dead and buried, speak to the next generation or to several succeeding generations in their work. Is that all, or is there more besides? In a painter’s life death is not perhaps the hardest thing there is.”

What is it that Van Gogh is saying? The hardest thing: to be valued in life as the artist one is. World-renowned only in death, his words beyond the grave paint a picture of the trauma of poverty. “I as a painter shall never stand for anything of importance, I feel it utterly. But if all were changed, character, education, circumstances, things might be different.”

Van Gogh waxes poetic the effects that poverty has on a person’s mental health. He even says money would only distract him from his work—a thought I’ve voiced myself, trying to rewrite feelings of worthlessness. We like to say the struggle is what “make us”, but it is not poverty that makes a person, it is poverty that defeats a person. Van Gogh committed suicide; inside these pages is a man defeated, unable to envision a future. I have suffered similar symptoms.

“… the new painters alone, poor, treated like madmen and because of this treatment actually becoming so, at least as far as their social life is concerned … the money painting costs crushes me under a feeling of debt and worthlessness, and it would be a good thing if this state of things could cease.”

If he was a madman, I am a madwoman.

Diagnosis does not diminish one’s genius. Becoming an artist—having the integrity to live by my internal compass in the face of adversity and adjusting my life’s entire focus to support my mental health through my practice, Memoirtistry®—has impacted my status in class and career. The loss of invitations because I can no longer pay my way has isolated me. The weight of the absence of a four-year degree is used against me, still; as if my life has taught me nothing. I am poor in the bank. I receive government assistance for food each month. I seek free things. I steal from corporations. I take only what I need and I use all of what I have. Nothing is without purpose. My desires for material things have waned as the money I do receive I pour back into my art.

What you see inside Dear Theo is the artist dismissed in life but capitalized upon in death—a story written of living artists pursuing their craft, that struggle is a “rite of passage”, distracting us from finding solutions for poverty to support mental health. Not everyone has the same opportunities afforded them, and when you are in poverty you are separate from society. You are a have-not, and are treated as such.

Van Gogh’s appearance, demeanor, lack of social standing, lack of college education, and poverty status affected his impression. He appeals to his brother to forgo comments on his dress—an oversized wool coat of his father’s and even Theo’s too-large hand-me-downs—as it is all he has. Things about him that could not be changed without money or generosity, criticized. When you live day-to-day, what little money you receive, you apply to the most pressing need. For Van Gogh, painting was a greater need than eating; he often fasted and moved about looking for the most affordable accommodations. “Society being what it is, we naturally cannot expect it to conform to our personal needs.”

The needs expressed within the pages were not exorbitant; most he mentioned were basic, human. He speaks of a dream life in an artist’s commune; a peaceful environment where money is not a constant pressure, so he could do his work the way his mastery and his mental health required. I have ached for the same. During one of his periods of being institutionalized for his “madness”, he commented, “They have lots of room here in the hospital; there would be enough to make studios for a score or so of painters.”

How much more could Vincent have created if his basic needs were supplied?

On July 17, I attended an artist focus group at the Equity Impact Center through Sweetwater Center for the Arts. The EIC partners with local nonprofit and social justice organizations to support the evolution of outdated and harmful systems. We discussed the needs of the artist and were fed and paid for our time. The EIC defines equity as “the creation of conditions and experiences of situational fairness, transparency, and accountability achieved when we apply differential resources to address unequal needs because people are situated differently.” The conversation revived my belief I can make a difference with my own difference.

The prosperity gospel of capitalism paired with the toxicity of manifestation keep those in comfort distracted from the reality that people are situated differently. Van Gogh was blessed to have the support of his brother, but often felt himself a financial burden to Theo. “I am glad you are of the opinion that it would be unwise to take some outside job in hand at the same time. This leads to half measures which make half a man of one.”

As Memoirtistry® has evolved, so has my discipline to continue in my practice. I’ve discarded more than 20 years in Corporate America; I’ve been a barback, a barista, a gas station attendant, a housekeeper, a gallery attendant, and a delivery driver. I’ve been told to go back to school or sell out by using methods that do not align with my values. But suffering a job I can do but am not meant to do, is taxing on my mental health.

What is the value of the death of an original?

Poverty causes one to come to terms with death; you feel it in the growl of hunger. In his paintings, Van Gogh’s poverty exists underneath the restored layers; we look, but do not see beyond the surface. Two days before his suicide, he wrote, “… at a moment of comparative crisis … my own work, I am risking my life for it and my reason has half-foundered. … You can still choose your side, acting with humanity, but what’s the use?”

What’s the use? Words of defeat. I wonder what Van Gogh would think of the brand his name has become. Would he feel proud of the financial success and fame, or feel… desperately forgotten? Dead artists stir conflict as I consider what is to become of my life’s work in death. I’m an original, too.

There is no greater pursuit than that of the creative spirit, but let’s not forget that prolonged resiliency without reprieve—surviving, not thriving—can lead us to death long before it is meant for us. I believe poverty killed Van Gogh, and we have to stop sacrificing the artists. 134 years later, organizations like the EIC are still rare to find.

“‘I am an artist’ … always seeking without absolutely finding. … ‘I am seeking, I am striving, I am in with all my heart.’”

Memoirtistry® is my beating heart. Similar to Van Gogh, I give my life for my work; and perhaps only in death can a life be realized.

Raptured in Biddle's Escape: Art as Therapy

Interactive Rapture art by Joseph Davis

We duck into Biddle’s Escape after collecting a handful of books from Fungus Used Books & Records. I’ve got Loghan Muha in tow, a preteen on the cusp of the Alpha and Z Generations. They, an artist becoming—youth evident, soul wise. There is a language without words, present mysteries understood between us, that I trust is universal, though not everyone finds the key.

Muha sits across from me at the checkerboard table facing the counter. Their curly explosion of hair gently tucked while reading Why Poetry? by Matthew Zapruder. I observe their movements to witness the subtlety of understanding. They glance up at me. “There are so many questions. I’ll need to pause to process.”

I pause with them, leaving our books on the table to explore the art inside Biddle’s. We play a favorite game of mine. If you could take any piece home, which would you take and why? Their eyes begin to move around the cafe. I revisit the piece I chose once before and decide it’s still the one I want: an androgynous alien statue. But another catches my eye and sends a trigger warning to my body. Dangling from a nail, a clipboard with a piece of paper boasting a sign-up sheet: “Next RAPTURE November 13, 2026,” with simple instructions: Friend Family Coworkers Politicians Yourself etc. Above the clipboard, a digital countdown in green:

864 Days 3 Hours 22 Minutes 41 Seconds

I experience a feeling of being watched, and I am; above me, the artist (and owner of Biddle’s) Joseph Davis, has affixed a plastic naked baby doll representing Jesus to a light-up cross on the ceiling. There are seven names signed up for The Rapture with various reasons identified. big fuckboy. manipulative bastard. stalked me nine years. good at lying.

Edgar C. Whisenant, a former NASA engineer, published 88 Reasons Why The Rapture is in 1988, and the United Pentecostal sect I was born into took it seriously. I was raised with a literal interpretation of the bible—taught that Present Life was to be spent in preparation for the After Life. Davis’ piece refers to The Rapture that is the second-coming of Jesus, where all believers—the Christians—will be called up to Heaven to praise God in eternal worship. Those left behind were to suffer imaginable horrors. My developing mind painted vivid images of the genocide of those who refuse The Mark of the Beast; a mark most will accept unconsciously.

I suffer vivid flashbacks of the days- sometimes weeks-long revivals. The sea of frantic adults, repenting their sins; the pastor blessing foreheads with oil. We line up to be baptized, singing hymns ad nauseam, wailing; hot tears on cheeks, quivering jaws, begging to be saved, asking God to spare us, to give us the gift of the Holy Ghost and bestow upon us the tongues of the language unknown. We can have it, and we want it. We want it more than anything. Adults run around the church, waving handkerchiefs, dancing when we are not to dance, falling onto the floor, exhausted from seeking the spirit. I was ushered into the experience—brainwashed from fear tactics, emotional manipulation—with my own baptism and confirmation of tongues at 7-years old.

I became accustomed to those in charge being unable to answer my questions and satisfy my need to understand what it is I was supposed to believe. We can’t escape fear because we can lose our salvation; an insidious cycle of dependency. I wondered if I would be strong enough to die for these beliefs unknown if I wasn’t raptured. Would the sacrificial gesture get me into Heaven? I am plagued by fantastical desires of martyrdom; an innocent named guilty, ashamed because I live, asking for forgiveness while being led to the guillotine without a fight. Jesus Complex-Post Traumatic Stress Disorder symptom.

Now I imagine a world—the biblical New Heaven and Earth—without Christians. All those who have abused my spirit, gone? Please leave me behind. Jesus’ return will save the rest of us from his own misguided followers. A list of names once marked for prayer in distant memory floods my brain.

I play the role of a stranger in Pittsburgh with pleasure; a memoir artist, I delight in rewriting history to showcase who I am now. I cannot continue to tend to versions of me unsupported. People change; it is not to be feared, but celebrated. Isn’t that what all those revivals were supposed to do for us? Receiving the gift of the Holy Ghost means you are changed. But the changed person, without the proper tools, can easily slip back into comforting [conforming] patterns of behavior. These patterns produce sin to be repented of and the change is forgotten. I come from a family who touts consistency in character and personality—“staying the same”—as truth while also believing in a Holy Ghost that is meant to change us. I’ve become estranged from those unwilling to respond to the very change they still beg for at the altars of my childhood. The tongues that “saved me” I now understand as mimicked behavior—a performance of salvation birthed from fear. In our desperation to prove ourselves worthy, we fake change that has not actually occurred. But change cannot be faked.

Inside of art, I grapple with hypocrisy.

My parent’s religion made me fearful of life, but the essence of the Holy Ghost—the superhuman ability to accept love and offer love without condition, which I have found accessible inside the uninhibited nature of creative flow—encourages me to live.

We cannot escape ourselves. Perhaps that’s what art is here to remind us. We ache for what we already have access to; it is the pain of remembering we were made to live, and we hate the reminder [we are not living], so we avoid looking. Death is not an end state; Jesus’ life as metaphor tells me this. I get lost in the metaphor because literal feels limited, with nowhere left to explore.

Loghan points to a piece on the ceiling—the one they’d keep—a portrait of a face shrouded in black hair with red contours around the nose, like tears running. “It looks like blood.”

Artist unknown

Tears of blood … how easily I am taken to Jesus on the cross.

At 12-years old, Muha’s point-of-view tells them time is plentiful; without the constant buzz of death on the horizon. A contrast to my experience living in these biblical End Times. To live is evil, and I must be saved from my own humanity. The Rapture as Art brought me home; I was taken to a past which reminded me who I am in the present. I am here, in Biddle’s Escape, and I am safe. I am saved. The key I have found in art—the universal language that Muha and I understand between us—exorcizes the demons in a way religion never achieved.

In Muha’s examination of poetry, asking Why?, they moved to Ember & Flame by Rasaja Wolfe. Loghan’s review of Wolfe’s wordplay struck a chord. “… I liked how the theme was mostly rebirth. It made me realize that letting go of what I was might help me grow and change for the better. I didn’t think that was a valid thing to do and that I always had to stick to who I was instead of inviting emotional growth.”

I am raptured by art; I die, and am resurrected inside of it.

Muha has found the key. Art is life is salvation. Living is the freedom Jesus died for. Being human, a masterpiece.

Eidos, 2019; T.H. Kainaros

Eidos, 2019; T.H. Kainaros

rumination;

the body rots

from this clarity of thought

death illuminates the dream

my face is not my face anymore

i am beyond

face

T|U|O|B|A

face!

inside the eyes,

a cave of secrets

where i rest on my throne

they see a decaying demon;

my protective shell

hiding

the alien

and not hiding her well

she drowned to get here

she is becoming one with the

d

e

p

t

h

s

where the blind fish grow

hers is the emanating g l o w you’ll sense when you make it this far

hers is the brightest light

in the darkest night

she >dims<

until

she

trusts

you may never see her directly

but you will know she is there

with you

always

<withyou/>

she is you

thethoughtsthebodyrotthethoughtsthebodyrotthethoughtsthebodyrotthethoughtsthebodyrottherottherottherottherottinggggggggggggggggggggggggggggggggggggggggggg

i am back from death—

alive,

and

still dying

choking on the water

s

w

a

l

l

o

w

e

d

WHOLE

please let me go

i’ll come for you next time